Please note this is an extended session. The talk will be given in Japanese with consecutive interpreting.

Rethinking the “Dual Dependence” of the Ryukyu Kingdom

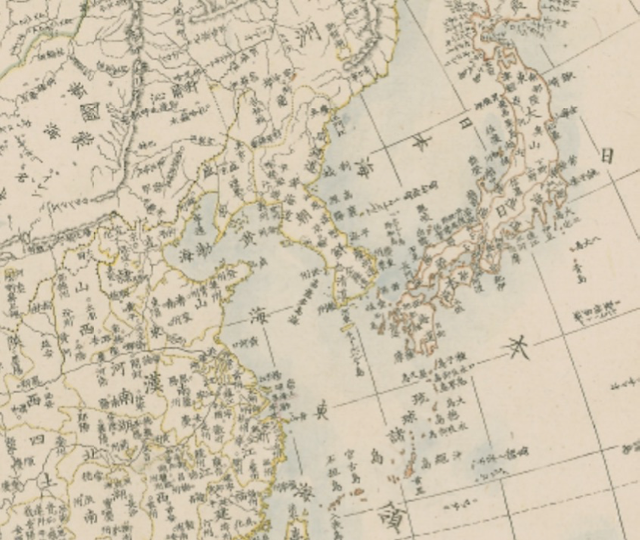

Before the Meiji government annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom (the so-called “disposition of Ryukyu”) in the 1870s, the Ryukyu Kingdom is said to have occupied a “dually subordinate” (J. ryōzoku; C. liangshu 兩屬) position to both Japan and China. Although such a description is by no means incorrect, this framing is insufficient for understanding the historical processes and debates which occurred surrounding the Ryukyu Kingdom’s status at the time. Indeed, while Japan, China and Ryukyu all came to use the term “dual dependence” to reference Ryukyu’s past, this paper will reveal how this two-character term meant different things to each of these actors and that these divergent perceptions underpinned how each of these actors responded to the annexation. What’s more, these alternative perceptions may yet have something to tell us about the historical trajectory of differences in how Japan, China and other states understand today's contemporary world order. This paper therefore aims to rethink this idea of Ryukyu’s “dual dependence” as a means to deepen our understanding of the contours and processes which underpinned the “modern” transformation of the traditional East Asian world order.

Before the Meiji government annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom (the so-called “disposition of Ryukyu”) in the 1870s, the Ryukyu Kingdom is said to have occupied a “dually subordinate” (J. ryōzoku; C. liangshu 兩屬) position to both Japan and China. Although such a description is by no means incorrect, this framing is insufficient for understanding the historical processes and debates which occurred surrounding the Ryukyu Kingdom’s status at the time. Indeed, while Japan, China and Ryukyu all came to use the term “dual dependence” to reference Ryukyu’s past, this paper will reveal how this two-character term meant different things to each of these actors and that these divergent perceptions underpinned how each of these actors responded to the annexation. What’s more, these alternative perceptions may yet have something to tell us about the historical trajectory of differences in how Japan, China and other states understand today's contemporary world order. This paper therefore aims to rethink this idea of Ryukyu’s “dual dependence” as a means to deepen our understanding of the contours and processes which underpinned the “modern” transformation of the traditional East Asian world order.

Click here to read extended abstract

Before the Meiji government annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom (the so-called “disposition of Ryukyu”) in the 1870s, the Ryukyu Kingdom is said to have occupied a “dually subordinate” (J. ryōzoku; C. liangshu 兩屬) position to both Japan and China. Although such a description is by no means incorrect, this framing is insufficient for understanding the historical processes and debates which occurred surrounding the Ryukyu Kingdom’s status at the time. This paper aims to rethink this idea of Ryukyu’s “dual dependence” as a means to deepen our understanding of the contours and processes which underpinned the “modern” transformation of the traditional East Asian world order.

During the Edo period, the Ryukyu Kingdom was conquered by the Satsuma domain and externally “concealed” its relations with Japan. China’s Qing government, which regarded Ryukyu as a tributary state, therefore did not know about the specifics of Japan-Ryukyuan relations. Furthermore, it was also for this reason that Qing China never perceived Ryukyu as occupying a position of “dual dependence” relative to itself and Japan.

After the Satsuma conquest of Ryukyu in the seventeenth century, the kingdom maintained a position of de facto autonomy relative to Japan and China, a situation which continued through until the Meiji annexation of the kingdom in the 1870s. What’s more, the Ryukyuans even concluded their own treaties with the United States, France, and Holland in 1850s.

However, after the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese modified their treatment of the Ryukyu Kingdom, doing away with their previous strategy of external “concealment” of Japan-Ryukyu relations and officially positioning the kingdom as a Japanese dependency. Following this, the Meiji government prohibited Ryukyu from engaging in relations with foreign countries, including China. However, only when the Japanese prohibited the kingdom from making tribute missions to China in 1875 did the Qing government realise that Japan had annexed the kingdom and sought to oppose this new state of affairs.

In late 1877, He Ruzhang, the first Chinese minister to Japan, arrived in Tokyo. As America had previously signed a treaty with Ryukyu in the 1850s, once in Tokyo, He Ruzhang contacted US representatives there and sought to convince them about the unjustness of Japan’s stopping of Ryukyu’s tribute missions to China and of its elimination of the kingdom’s autonomy. Moreover, according to a similar line of argumentation, he advised several Japan-based Ryukyuan officials to petition the help of the three powers the kingdom had previously signed treaties with for combatting the actions of the Meiji government. And, in October 1878, he officially submitted a protest to the Japanese government. However, this act only worked to incense the Japanese and encouraged them to push ahead with the formal annexation of the Ryukyus in 1879.

Needless to say, the Qing government did not recognise Japan’s annexation of the Ryukyus, and persistently appealed to the Meiji government for a return to the status quo ante. The crucial point of contention in the Sino-Japanese dispute concerned the validity of the Qing’s argument that Ryukyu was an autonomous polity, using such language as “jishu/zizhu” 自主 and “jichi/zizhi” 自治 (both translating as autonomy) and “midzukara ikkoku wo nasu/zi wei yiguo” 自為一國 (translated as “nationality” at the time) to articulate this position. The Chinese advocated for Ryukyu to continue to be perceived in this way as its “autonomy” was a status which was indispensable for perceiving Ryukyu as a tribute state. However, the Meiji government refused China’s appeals and its argument that Ryukyu constituted an autonomous polity (zizhu/zi wei yiguo) due to Ryukyu’s past dependence on early modern Japan (J. fuyō 附庸). This paper contends that the analysis of this historical process will help us understand the multiple meanings encompassed by such terms as jichi/zizhi and midzukara ikkoku wo nasu/zi wei yiguo, which encapsulated the characteristics of the traditional world order of East Asia.

Ultimately, China and Japan failed to reach an agreement on the Ryukyu controversy. This situation was, for instance, typified by the divergence in opinion which emerged on both sides about whether a two-way or three-way split of the islands was most apposite in the negotiations which took place after ex-US president Ulysses S. Grant’s mediation of the dispute. This does not, however, deny the historical significance of the annexation and the ensuing debates around it.

Indeed, while Japan, China and Ryukyu all came to use the term “dual dependence” to reference Ryukyu’s past, this paper will reveal how this two-character term meant different things to each of these actors and that these divergent perceptions underpinned how each of these actors responded to the annexation. What’s more, these alternative perceptions may yet have something to tell us about the historical trajectory of differences in how Japan, China and other states understand today's contemporary world order.

OKAMOTO Takashi is professor in the Department of Historical Studies, Faculty of Letters, at Kyoto Prefectural University. Born in 1965, he graduated from Kobe University and obtained his Ph.D. in literature from Kyoto University. Okamoto served as associate professor at the University of Miyazaki before assuming his current position, where he specializes in East Asian and modern Asian history. Okamoto has published many books on modern Asian and Chinese history, of which three have won awards: Kindai chuugoku to kaikan [China and the Maritime Customs System in Modern Times] (Nagoya: University of Nagoya Press, 1999), recipient of the Masayoshi Ohira Memorial Award; Zokkoku to jishu no aida: Kindai Shin-Kan kankei to Higashi Ajia no meiun [Between Dependency and Sovereignty: Sino-Korean Relations and the Destiny of East Asia] (Nagoya: University of Nagoya Press, 2004), winner of the Suntory Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities; Chugoku no tanjo: Higashi Ajia no kindai gaiko to kokka keisei [The Birth of China: International Relations and the Formation of a Nation in Modern East Asia] (Nagoya: University of Nagoya Press, 2017), recipient of the Kashiyama Junzo Prize and the Asia-Pacific Prize. Other works available in English include A World History of Suzerainty: A Modern History of East and West Asia and Translated Concepts (editor, Toyo Bunko, 2019/Adobe Digital Edition PDF); and Contested Perceptions: Interactions and Relations between China, Korea, and Japan since the Seventeenth Century (JPIC, 2022).