to

Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Room 8 & 9

About

Abstract

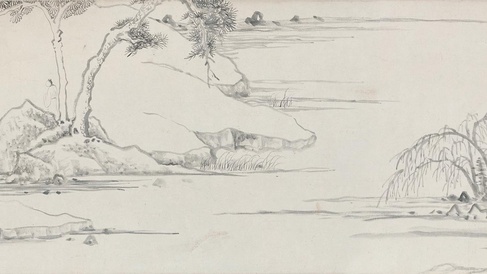

During the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644), tea drinking underwent significant transformations with the shift from powdered tea to loose-leaf infusion. This change is most readily visible in material culture: deep bowls used for whisking tea fell out of favour, while teapots designed for steeping leaves became essential. Although prized spring water had been ranked and theorized since the Tang dynasty, the Ming transition to loose-leaf tea coincided with a new artistic engagement with springs and their surrounding landscapes. Brewing practices now foregrounded water choices more conspicuously, prompting heightened visual and textual attention to the sourcing, quality, and emplacement of fresh water. Scholarship has largely approached Ming tea culture through its social dimensions, emphasizing taste, sociability, and literati self-fashioning. This paper instead adopts an eco-art historical perspective by examining landscapes by artists such as Shen Zhou (1427–1509), Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) and their contemporaries, in which tea, springs and acts of brewing appear. While such images articulated connoisseurly knowledge and social distinction, their repeated focus on specific springs also signals an emerging visual sensitivity to the scarcity and exploitation of valued natural resources. Drawing on paintings, poetry, tea manuals, ceramics, and calligraphy, this study argues that mid-Ming landscape painting registered a shift in attention from generalized scenic ideals toward localized ecologies of water. By foregrounding water as a material and ecological actor, the paper examines mid-Ming paintings as a site of negotiation between aesthetic cultivation and environmental limitation and reflects on the gentry’s role as a force that both shaped and was shaped by regional resource ecologies.

Author Bio

Henning von Mirbach is Assistant Professor in Early Modern Chinese Art at the University of Cambridge. His teaching focuses on the painting and visual culture of late imperial China (ca. 1200–1800), with particular emphasis on landscape painting and its local and global entanglements. His research reconsiders the history of early modern Chinese landscape painting through questions of commemoration, gender, and spatial memory. He is currently completing a book manuscript titled Maternal Landscapes: Women and the Politics of Commemoration in Early Modern Chinese Art, which centres mothers and grandmothers as key figures in artistic production, commemorative practice, and the formation of site-based memory. Originally from Bonn, Germany, Henning holds terminal law degrees from the Université Paris X–Nanterre and the Universität Potsdam and received his PhD in Chinese art history from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Before joining the University of Cambridge, he taught at The Courtauld Institute of Art in London and at National Taiwan Normal University in Taipei.

Image Caption

Wen Jia 文嘉 (1501–1583), Mount Hui 惠山圖, 1525. Handscroll, ink on paper, 23.8 x 101 cm. Shanghai Museum, Shanghai.